Oak Alley Plantation: If These Old Oaks Could Talk…

Which came first, the house or the oak trees? That’s a persistent question at Oak Alley Plantation in Vacherie, Louisiana. Built in the early 1800s and listed as a Designated National Land Mark, this sprawling four square Greek Revival antebellum mansion sits along the winding west bank of the Mississippi River. The answer, according to the Oak Alley Plantation’s research, after considering the evidence and logistical size and placement of the live oaks is: the house!

Oak Alley Plantation Architecture

Oak Alley Plantation’s architecture mimics the ancient Greek temple, although, the influence of New Orleans’ sultry months is evident in the structure’s 16-inch thick brick walls lathed with plaster to keep the hot air out and the cool air within. The square house is surrounded by 28 Doric columns and porches on the first and second floors. This protects the interior living spaces from excessive heat and sunlight. The architect positioned French doors on opposite sides to encourage maximum air circulation. The presence of high ceilings, long windows, and a central hall lend to the elegant efficiency of its design.

Jacques Télesphore Roman originally built the plantation house as an inspiration to lure his wife, Celine, away from the exciting bustle of New Orleans. Jacques, a French Creole business man, also wanted his own sugarcane plantation. After three years, slaves completed the house’s construction in 1839.

During the Roman’s occupancy, the plantation included: the “big house,” barns, sugar mill, and 1200 acres of land. Jacques preferred the plantation life much more than his wife, and although she spent some time at Oak Alley, it wasn’t long before she lived mostly at their “in town” residence.

As time passed, the riverboat captains who paddled along the nearby banks, coined the plantation as “Oak Alley” because of its magnificent row of live oaks spanning the distance between the river’s edge and plantation’s front door.

Oak Alley Ghost Stories

An old house is not complete without a few ghost stories of “a touch on the arm, a candlestick inexplicably flew across the room, equipment strewn about the floor, which the day before had been neatly stowed, empty chairs rocking unison, sounds of horses, and a child crying.”

The Live Oaks of Oak Alley Plantation

So, who planted the 28 Live Oak trees that create Oak Alley Plantation’s spectacular and famous 800 foot alley leading from the river to its front door? That’s a hot debate. Some say it was an unknown French settler nearly 300 years ago. Oak Alley’s Director of Marketing Hilary Loeber says, “Using land records and archaeology reports, we have learned that this story is not possible.”

“alley” means “canopied path” in French.

That doesn’t make the story any less romantic and mystifying. Evidence points to the oaks getting planted or transplanted sometime after 1807 because of the “meander of the river and the existence of a significant area of batture. The river was too close and the batture encroached even further.”

“Batture refers to the alluvial land between the low-tide of the Mississippi and the levee. The word “batture” comes from the French word “to beat,” referring to the land “beaten” by the river.”

In addition, “because some of the trees are large enough to be 200-250 years old, and it is impossible that they were planted as young saplings (early 1700s), then they were ‘mature’ (over 10-15 year) trees when they were transplanted. Such transplanting was done, but it was an enormous undertaking—even today, moving Live Oaks is something arborists try to avoid. It required a planter with resources (large number of slaves and access to specimens) and a planter who could afford to dedicate these resources (locating specimens, slave labor, keeping the trees alive) to what was basically a massive garden project.”

[Click on a photo to view as slideshow.]

If we take this evidence as fact, there are some hypotheses that abound:

“Option 1: Jacques E. Roman. While a possibility, this is unlikely in that Sec. 7 was not the family’s main residence. Jacques E. was still establishing his family in St. James at the time of his death in 1811, and his records show a man interested in operations and business, not horticulture. It is possible, however, that he planted the 2(3?) trees close to the house.

Option 2: Any of the farmers who owned the land between 1811 and 1820. Chabert (4 arp. ) Lebeouf (2 arp.) Widow Louis Arcenaux (2 arp.) Widow Baptiste Arceneaux (2 arp.) each owned small farms—each amounting to a sliver of land w/ frontage. None had the labor force or money to throw at a gardening project of this magnitude.

Option 3: Valcour Aime 1820-1836. First possible contender with the resources and vision to embark on a design project of this scale. We must keep in mind that based on his diaries, the amount of collaboration between he and Jacques T. was significant, so he not only had his own resources, but access to his brother-in-laws as well.

Option 4: Jacques T. Roman 1836-1848. Second contender with the resources and vision to create the alley. The batture at this point had been tamed along the St. James river, as planters constructed levees and firmed the line between their estate and the Mississippi. His health declining by the mid 1840’s however, makes the planting (if it was Jacques) in the late 1830’s or early 1840s.

Option 5: A combination of Jacques T. and Valcour. Seeing how much they collaborated, it is quite possible it was a joint project somewhere between 1820 and 1840. In order for some of the trees to be as large as they are, this would mean they moved trees up to 20 years old, a monumental feat.”

For arborist-enthusiasts, here’s the “how”:

“The first three trees closest to the house (definitely the first two) were planted prior to the house being built as they are slightly overset, consistent with the placement of the river road during the 1800’s. The rest of the trees were transplanted in rapid succession shortly after the house’s construction. All of the transplanting was done by enslaved persons, likely belonging to both Valcour and JT. First, physics were used to move the trees into place via a wagon sized dolly/handcart. A tree that was about 30 years old would be selected from nearby. Any older and the tree would be too large and heavy to be moved. A huge pole would be driven into the ground next to the tree and the tree tied to the pole. Pulleys and a team of mules or oxen would pull the thousand pound tree out of the ground as the rootball was dug out. The large tree dolly would move the tree to Oak Alley Plantation and it would be lowered into its new location. Second, engineering would be needed to keep the tree watered. Canals would be dug from the levee to the tree to keep it hydrated. Too much water, and the tree would drown; too little water, and the tree would die of thirst; way too much water and the countryside would flood. The Enslaved community were successful, and Oak Alley still has its complete alley of 28 live oaks.”

Why was the oak tree alley created?

“They [the Live Oaks] were transplanted for both beauty and purpose: to create a tunneled view to magnify the plantation home’s beauty as well as to help channel the river breeze to cool of the home.”

Fun Fact: “Oak Alley has no Spanish moss, and we have no idea why. The old story was Mrs. Stewart didn’t like it, but recently we noticed in a photo from before she moved in that there was no Spanish moss.”

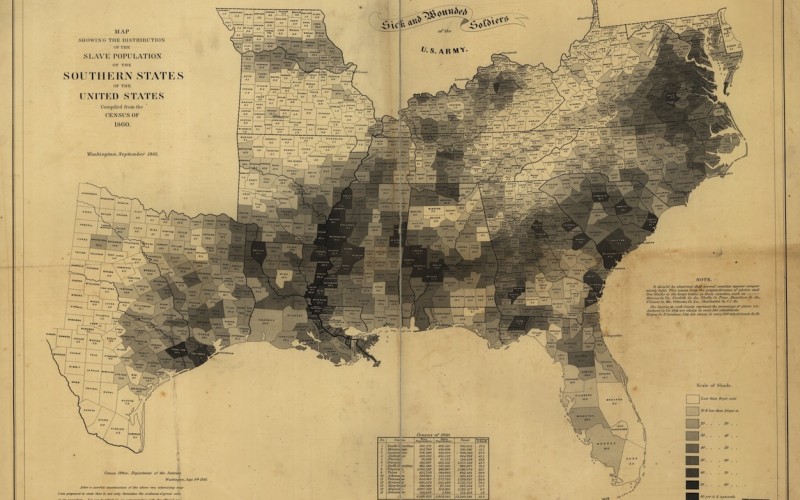

Slave Life at Oak Alley Plantation

Slave life was difficult at Oak Alley Plantation. The field slaves labored in the sugarcane fields, and then, in the mill during the harvesting season. The field slaves “spent time weeding and irrigating hundreds [and] hundreds of acres of sugarcane stalks, using machetes to clear the fields, primarily a male slave job. Then, running the sugarcane though the sugar house machinery to create sugar cane juice, which would later be turned into molasses and sugar. House slaves numbered one for each family member. If they failed at their tasks, the house slave was sent to the fields.”

Slave life was difficult at Oak Alley Plantation. The field slaves labored in the sugarcane fields, and then, in the mill during the harvesting season. The field slaves “spent time weeding and irrigating hundreds [and] hundreds of acres of sugarcane stalks, using machetes to clear the fields, primarily a male slave job. Then, running the sugarcane though the sugar house machinery to create sugar cane juice, which would later be turned into molasses and sugar. House slaves numbered one for each family member. If they failed at their tasks, the house slave was sent to the fields.”

“Repairing roads and levees was ‘women’s work’, while their more expensive male counterparts were organized around tasks immediately related to sugarcane cultivation, such as cutting wood, irrigation, and machinery repair.”

Oak Alley Plantation’s present slave quarters were reconstructed in the 1900s by its last owner, the Stewarts. According to Hilary Loeber, “Oak Alley recently completed a research project that took over six years and afforded us the opportunity to share new information and untold stories.”

The Oak Alley Foundation has cultivated a Slave Database on its website.

Oak Alley in the 21st Century

Although Oak Alley Plantation survived the Civil War structurally, it could not withstand the changing economics of post-war. The plantation changed hands many times and fell into disrepair. In 1925, Josephine Stewart and her husband Andrew purchased the plantation to use as a cattle ranch and restored the neglected house and grounds. Over decades in residence, the Stewarts opened their doors the plantation for parties, charities, 4-H groups, garden clubs, and many other community events. Josephine Stewart reintroduced sugarcane to the plantation in the 1960s. Mrs. Stewart was the last owner in residence until 1972, and the reason why Oak Alley Plantation is now open to the public. Although the Stewarts did not have children, their nieces and nephews run the Oak Alley Foundation today as a historical attraction, restaurant, event space, and B & B.

“The largest tree, named the “Josephine Armstrong Stewart,” has a girth of 30 feet in circumference and has a 127 feet limb spread. Its namesake, Ms. Josephine, was the last owner of Oak Alley, and it was she who established the Oak Alley Foundation, which preserves the plantation today.”

Though they purchased it to serve as a working ranch—which it did for many decades—Josephine began to truly revive the mansion to its greatest glory not long after moving in, including the reconstruction of the slave quarters. “Mrs. Stewart even converted one extremely large chicken coop—a building from the previous owners…into an indoor pool.” At present, the grounds include a 1920’s formal garden, an old car garage, blacksmith’s shop, a Civil War tent with live historical interpreter, reconstructed slave quarters, and the Stewart cemetery.

[Click on a photo to view as slideshow.]

Hollywood & Writers at Oak Alley Plantation

Some might say life is slower in the South; the intense heat and humidity demands it. In a time without air conditioning, slow is better. That might be why Oak Alley Plantation was chosen as the movie location for The Long Hot Summer, starring Paul Newman, Joan Woodward, and Orson Wells. The screenplay is based on several works by William Faulkner and a Tennessee Williams’ play Cat on a Hot Tin Roof. A few famous visitors to Oak Alley Plantation include: Brad Pitt, Tom Cruise, Bette Davis, Joan Rivers, Jennifer Coolidge, John Malkovich, Clint Eastwood, Cecily Tyson, Laura Dern, Dian Lad, Rob Lowe, and more!

[Click on a photo to view as slideshow.]

Touring Oak Alley Plantation

“A plantation is not a house,” and so, “there is no cattle call and pods of people huddling together waiting for their group’s turn,” said Hilary Loeber.

Today, visitors are encouraged to explore the antebellum plantation, with its restored structures and grounds, as a historical exhibit filled with artifacts, stunning architecture, and cultured landscape. Oak Alley Plantation is an individual experience, whether you immerse yourself in slow travel and study a few aspects, or you enjoy a bit of all of it.

Related Blogs: